Enhancing cognitive performance – Latest from the Hintsa Lab

Have you heard about the new generation of San Franciscans who are experimenting with micro-doses of LSD to improve focus and creativity? I read about this ‘interesting’ approach to enhancing cognitive performance in the Financial Times, a couple of months ago, and the article has stuck with me.

The journalist who penned the feature interviewed a start-up founder, who reported a number of benefits after micro-dosing. However, the founder went on to reveal that he couldn’t be sure whether the reduced stress and enhanced performance he felt had a causal or correlational relationship with the LSD; they may have also been related to a new project management system Asana the team began to use, at the same time.

It got me thinking, if we can’t tell the difference between a software as a service and a psychedelic substance, perhaps we’re not addressing the root cause of the focus and fatigue challenges that many of us face at work and home.

In the second edition of The Hintsa Lab, where we’ll continue the theme of cognitive enhancement through the structure we introduced in the previous Hintsa Lab blog: one project we are working on, one interesting article that we find worth reading, and one question to consider.

What we are working on

Have you ever considered the relationship between sleep and anxiety? As I write this article, over 50 people are participating in our new study tracking sleep, activity, and daily patterns in their cognitive performance, mood and anxiety. The majority of the tracking is taking place via an academically validated wearable and smartphone application. This relatively cheap and scalable approach to data collection means that we are able to measure more variables, in a greater number of people, at higher frequency. The definition of our insights is enhanced and, because the data points are ‘time-locked’, we are better able to explore correlations between variables and test new hypothesis.

We’re particularly interested in the relationship between sleep, anxiety and cognitive performance. A recent paper by Sullivan & Ordiah (2018) described this relationship using data from a nationwide telephone-administered survey participants reported how often in the past month they felt nervous, hopeless, restless/fidgety, depressed, the number of days their mental health was “not good”, and the number of hours of sleep they received per day. The findings suggest a strong association between sleep duration and mental health symptoms, noting that even minor sleep insufficiency is associated negative symptoms.

While this study provides some interesting insights, based on a large population, the fact that it relied on seIf-report and participant’s memories from the previous month introduces some limitations. I’m excited to delve into the data of our own study and explore this relationship in our participants, who will be tracking their mental state more regularly, and recording sleep using a more robust method.

Recommended reading

I know I said one article or paper, but I can’t help myself. This month I’m suggesting a documentary film… and two papers…

I recently watched “Take your pills”, a new documentary on Netflix. The film takes a critical view of the increasing diagnosis and pharmaceutical treatment of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) in the United States, as well as the ‘off-label’ use of medications such Ritalin and Adderall, in pursuit of cognitive enhancement. Charting the history of these potent stimulants, the filmmakers take us on a tour of cultural, scientific and ethical considerations through a series of interviews with researchers, patients, users and other commentators.

I have a long-standing interest in cognitive performance enhancement, so I was unsurprised to hear about the prevalence of ‘smart-drug’ use in students and professionals looking to gain an ‘edge’. The use of these powerful stimulants has become normalised on many campuses and in the high-rises of global corporations. However, it was curious to note that few of the ‘self-experimenters’ interviewed for the film seemed to have explored what might be going on in their brains and bodies when they consumed these substances, beyond their own subjective experience.

The findings of the scientific research that were discussed in the documentary were also of interest, particularly with regard to the impact of ‘smart drugs’ in healthy populations. Contrary to popular belief, the evidence for the cognitive performance-enhancing effect of many smart drugs is far from conclusive. So why are they so popular? While the evidence for measurable cognitive enhancement is mixed, there’s more general agreement that the drugs make healthy users feel better about the work they are doing. In practise, taking smart drugs may not make a study session more efficient directly, but that the fact that you feel better while studying may incentivise you to stick at it.

If you decide to watch the documentary, and if you’re interested to explore the subject in more detail, you may want to the two following papers.

- Smith & Farah (2011) “Are Prescription Stimulants “Smart Pills?” explores questions such as whether prescription stimulants enhance cognition for normal healthy people, based on a review of the epidemiological and cognitive neuroscience literature.

- Basso & Suzuki (2017) “The Effects of Acute Exercise on Mood, Cognition, Neurophysiology, and Neurochemical Pathways: A Review” provides some more sustainable ideas for enhancing cognition, with more favourable ‘side-effects’.

While looking for the quick-fix, hack or solution in a pill is tempting, some of the best evidence for the enhancement and maintenance of cognitive performance relates to physical activity. The second paper summarises the cognitive and behavioural changes that occur with acute exercise in humans, which include improved executive functions, enhanced mood states, and decreased stress levels.

If you’re looking for a way to upgrade your brain, I’d suggest that being more active, even if that is simply getting away from your desk for a short-walk, may be a more potent cognitive performance enhancer than many smart-drugs, and likely comes with more tangential benefits and fewer side-effects.

Question to consider

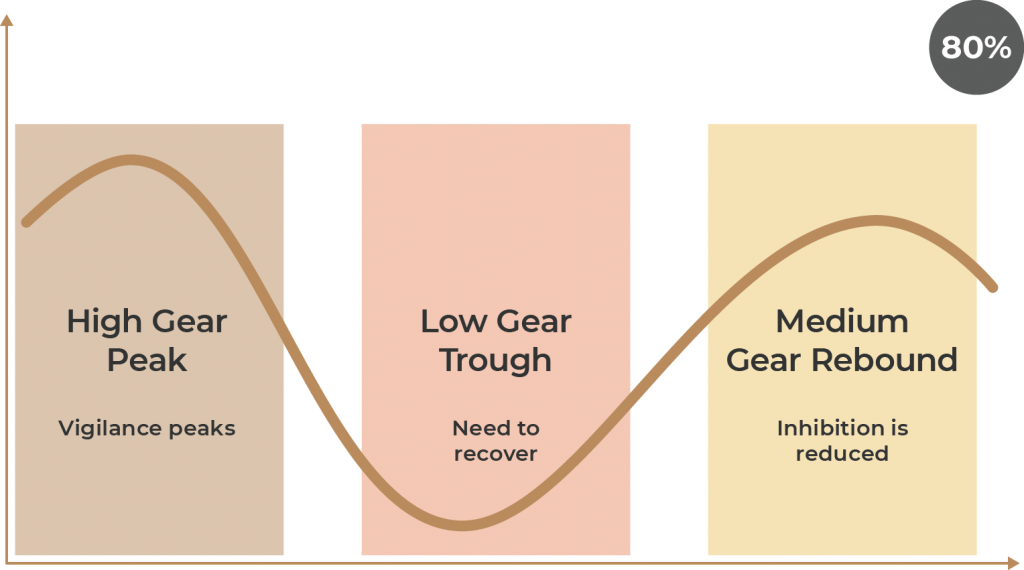

All humans follow a rhythm of peak, trough and rebound during their waking hours. During the peak, we are most vigilant and perform better in analytic tasks. During the rebound inhibition is reduced, and we may be more suited to work requiring insights and creativity. In our trough, we are much more likely to experience poor health, ethical and productivity outcomes.

For around 20% of people, the pattern is reversed, depending on chronotype (whether you are a morning or evening ‘type). The rebound is experienced in the morning, with the peak towards the end of the day, and into the evening. However, according to some research, 2:55 pm is the least productive time of day for most workers.

“How effective are your breaks?”

How do you spend your breaks? Filled with pseudo-work, mindlessly scrolling e-mail or checking social media. Evidence suggests that the best breaks involve us:

- Getting away from our desk

- Doing something active

- Interacting with people that we like.

Before you get on with your next task, I encourage you to take a step back, move around, speak to someone and recharge, before you rebound into your day.

I hope you enjoyed this edition of the Hintsa Lab blog. Come back next month to find out more about what we have been up to.

The Hintsa Lab is a blog series showcasing the latest news from our Innovation Lab. In each article, we will reveal something we are working on, something worth reading, and a key question to consider.