Are Parents of Small Kids at a Disadvantage for Cognitive Performance? The Surprising Science Why They May Not Be

I slump into my chair at the office. Tired, I stare at my to do list. I should feel rested and refreshed, but I can hardly even see the list. I’ve been up three times during the night to chase away monsters for my 1-year-old. I’ve battled it out with my 3-year-old whether she needs shoes to go out (yes, she does), whether she can throw her breakfast on the floor (no, she can’t), and whether she can bring her favourite purple dinosaur to daycare (I gave up: yes, she can). And then I’ve left her at kindergarten, crying and screaming, to go to work. It’s only 8:30am, but I feel like I’ve already given all I have.

Being a parent to young children is not the ideal setting for cognitive performance: the sleepless nights, the vicious circles of all kinds of nasty flus, the drop-off, pick-up and hobby logistics that limit the work day. In our society the ”ideal” worker is one who can devote themselves entirely to work, with few responsibilities and distractions. Children are definitely a responsibility, and most certainly a distraction.

But it may not be all negative

Even so, parenting has not had an entirely negative effect on my cognitive performance. Kids indeed force shorter workdays, demand energy, and cause very real challenges of managing work and family. At the same time, I feel like I today get more out of my work than before kids. Why? As a parent, one thing has clearly improved: goal-orientation. With kindergarten pickup looming as a deadline, I become razor-focused on my goal. No distractions, no chitchat, no firefighting. Get. The job. Done. At best, I manage to get into states of flow at work that make me lose sense of time and place, giving me an energy boost to last through the evening.

As a parent, one thing has clearly improved: goal-orientation

Surprising? Maybe. But research partly confirms my subjective experience. There is actually surprisingly little scientific evidence to show that family consistently worsens work. In fact, some research shows how parenting can boost performance. In a fascinating series of studies researchers looked at how employees’ family structures and after-work activities affected their work absorption.

Their finding: single, childless employees experienced lower work absorption than employees with other family structures. Why? The researchers found that work and home tasks are similar in nature – they are obligatory and goal-oriented – and thus reinforce each other. In short, a parent’s domestic responsibilities strengthen the work mindset, thus allowing greater psychological immersion in the work role. Apparently, parents may be able to get into better flow.

The power of managing your own cognitive performance

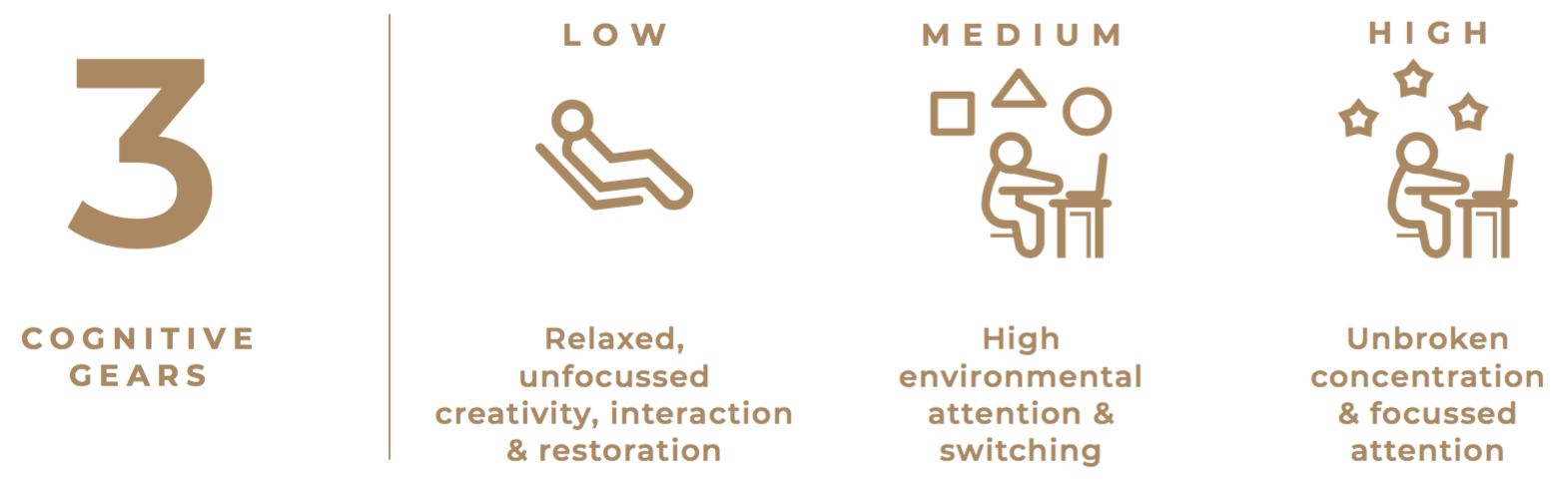

Positive or negative effects aside, the one thing kids have taught me is how important it is to mindfully manage my cognitive performance. So when I a few years ago heard researcher James Hewitt (nowadays a dear colleague, but back then merely a charismatic speaker) talk about cognitive gears, something clicked for me. This was the framework I needed. Without knowing it I had been applying the principles of cognitive intensity, but James’s ideas provided me the springboard to further develop my routines for work and home.

In my own words, I’ll describe James’s ideas about knowledge work and the three levels of cognitive intensity, peppered with my tips on how I’ve put it into practice as a working mother of two. First, the three levels of cognitive intensity:

- Low intensity: Rest, breaks, social events, lunch, workouts, etc. Anything that soothes your mind and allows recovery

- Middle intensity: Meetings, urgent tasks, email, conference calls, multitasking

- High intensity: Focused and undisturbed work, allow creativity and flow

We usually do what we shouldn’t: we get stuck in the middle. We sit in meetings, respond to emails, and work on five different things simultaneously. We do a lot, but few things well. James’s ethos is that we should work our mind like endurance athletes train their body: minimise the middle, and up the low and high intensities. More focused work, and much more recovery. Easy to say, harder to do. You can download our white paper to learn more about how to use your cognitive gears.

In my own work I’ve learned how important it is for me to find and stick to proper rhythms of work and rest. But knowing is different from doing. So here are some of the concrete things I do to make sure I get enough high and low intensity.

Take the time: Block focused work in your calendar

This is the simplest tip, but it just works. Every week I block three or four 2-3 hour sessions of deep work. For me mornings are prime time, so a few mornings a week I work away from the open office, on things that require my undisturbed attention. I don’t always make it, but 80% is enough to keep my brain happy and creative. And I can’t even begin to describe the euphoria I can feel after having been fully absorbed by work for a few hours.

Every week I block three or four 2-3 hour sessions of deep work

Naturally, doing this also means I have some days with nine back-to-back meetings. On those days, however, I find it easier to let go of the illusion that I’ll get any “real work” done. I simply accept it as an all-meeting day and take consolation in knowing my deep work sessions are booked.

Be ready: Use transitions and rituals to ”change roles”

Having the time for rest and high intensity work is not enough – you need to be able to use the time. So what if you don’t ”feel like it”? It’s easy to get stuck in ”mom mode” or ”work mode” – especially when there’s a child desperately screaming your name or when there’s a colleague desperately awaiting your input. I use the transitions between home and work to deliberately change roles and prime my brain for the next phase.

On my walk to work I usually listen to a work-related podcast, and on the way back from work I listen to music. Importantly, I try to minimise email and Slack during these transitions. That way I’m much more ready to dive in and be focused when I get to work, or alternatively, wind down and switch off when I get home. Research has, in fact, found that organisational rituals (e.g., morning coffee in the break room) can help employees transition to and from work in ways that improve work absorption.

I use the transitions between home and work to deliberately change roles and prime my brain for the next phase

I admit, some days I’m still worked up when I get home. Then I do one more thing. I pause before unlocking the door, thinking ”Who is the person I want to be in there?”. Rarely do I picture a frazzled, annoyed mother (which doesn’t mean I never am). That visualisation helps me drop work-me and start switching off.

Stay in gear: Use visuals to maintain focus

Besides deleting distractions (email and phone namely) when sitting down to work, I use strategically placed reminders of my to do list to keep me focused. For me there’s something so fundamentally satisfying with crossing something off my to do list that if I have a note next to my laptop with my three next tasks, then they’re bound to get done (sometimes I even add tasks I’ve already done to the list, merely for the satisfaction of crossing them off again).

I use strategically placed reminders of my to do list to keep me focused

This type of visual prompting has been found in studies to help with planning and refocusing on work, e.g. employees using the strategic placement of calendars, post-it notes, to do lists, and the like to redirect their focus back to work, and not let focus slide over to their free time activities.

The beauty and the paradox of life

All of this is not meant to say that someone is ”better” than someone else at cognitive performance. Parents of small children will, on average, remain at a disadvantage when it comes to e.g. sleep quality compared to our child-free peers. And our different life situations will remain varied and ever-changing, resisting to be reduced down to a binary of kids or no-kids. Our individual genetics and behaviors are in the end what matter the most.

Instead, my message is this. All my fellow parents, overwhelmed by combining work and family: studies like these are good news. Human life is set up in a way that we have our kids and build our careers at the same time. This is unlikely to change. When we’re at peak fertility, we’re also at peak professional development. Hence, we need to balance promotions with pregnancies, learning new work skills with learning to walk & talk, professional advancement with personal staying in the moment. Yet, with the beauty of life’s paradoxes, it may be this very complexity which, if managed correctly, can set the stage for not only a fulfilling family life but also absorption and success at work.

Knowing this helps me stay happy and calm – and that, my friends, is the ultimate boost for cognitive performance.

Whether you are a parent of small kids, lead an organisation or team with parents as employees, or generally are interested in cognitive performance, we’d love to help. Leave your contact details below and we’ll be in touch as soon as possible.